Welcome

My name is Joan. I’ve just turned 87 and I’m a Balmain girl. My mum was born in Balmain, and it was where she died. It was where my parents raised my three siblings and me, and it was where the family home was for over 50 years.

I had my two children at Balmain Hospital in the 1960s. In fact my siblings’ children were all born there too.

I’ve got stories and memories to share about life in Balmain from the late 1930s to the 60s, and beyond. I’m now sharing them here. It’s about how a Balmain girl views the world.

Most of what I’ve written was originally in longhand, written over decades on sheets of note paper. Not everything is in order and I may have repeated myself in some bits. A few things have been left out, some by accident (and some on purpose!).

Having this website gives me a chance to edit, and to add bits I’d forgotten. It’s a big task but they are precious memories, at least to me and to those who have shared my life.

I know there are people who are still alive who may beg to differ with my telling, and that’s to be expected. For now, I wish you happy reading.

How to navigate this website:

All the stories and titbits are presented below, in a single page. You can decide to start reading here and scroll down to the end (there are regular links you can select to take you back to the top of the page at any time).

Alternatively, you can use the menu below. If you select one of the section titles that are underlined, you’ll jump to those sections (so you won’t have to scroll down to find them).

Section menu:

- A story of dreams unfulfilled

- Stories from the 1930s and 1940s

- Stories from the 1950s

- Stories from later on

You can select to return to this menu at the end of each section.

A tale of dreams unfulfilled

I think about my father a lot, and dreams unfulfilled.

How many people have dreams and ambitions that will never be realised? I believe countless millions. I ask myself how many did I have? Maybe just two or three? Not very important to anyone else but the direction you take can shape the rest of your life.

Maybe I was not strong enough and didn’t have what it took to make all my dreams come true. Now I will never know. Growing older, other things are more important. I guess a lot depends on your background and family situations.

Many do make the breakthrough regardless of all the obstacles and setbacks.

When you come from a working class background with poor parents in a poor suburb, even with lots of love, it’s not easy.

I will continue on about my dreams at a later time because a more important person than me never had a chance to fulfil his dreams: my very much loved father, David Norman D________.

Dad could sing from the heart with a voice so natural and rich that he could leave many famous singers floundering. But what chance did he have? The third youngest of four boys and a sister, struggling through the great depression like all the other families at that time.

When you are the only one working in a family of six at the age of fourteen, with a very sick father and not much education past the age of twelve, working three jobs helping to keep a family together – one job before school selling papers, one working for the milkman after school, and on weekends working as a cockatoo (a look out) for the SP bookies.

Did he have a chance?

I am his daughter, Joan. I have heard him sing since I can remember him — which is a long time, because he was only 17 when he married my mother, Doris (Dot), in 1937, and I was born that same year.

He never had a lesson but he worked at the old Tivoli Theatre which was located in the railway area of Sydney. He, with his three brothers, sold Peter’s ice cream at interval.

Maybe he listened and learnt from the many artists that appeared there. Artists like Gladys Moncrief, George Wallis Sr, George Formby, Tommy Trinder and too many others to name. He used to tell me about them all. Mum used to take me there to see the shows and pantomimes. I used to wave to dad over the balcony.

We always sat in ‘the gods’ at the Tivoli because it was the cheapest. To get up there, there must have been at least 100 steps. I used to say to mum, “we are going to heaven!”. We only went to the pantomimes at Christmas. I would have loved to sit down the front as they used to throw out lollies and we never got any because they wouldn’t reach us way up there.

As I think about the Tivoli it has come back to me that my mother told me that her grandmother was the flower-seller outside of a nighttime and, that she was run over by a horse and cart and killed. I must try and find out more, but I can’t ask mum as she is not with me anymore.

Stories from the 1930s and 1940s

Dot and Dave, my mum and dad

Mum was a Balmain girl who worked at Lanham’s laundry at Rushcutters Bay. It was here she met my dad, David, who was from Paddington. They fell in love and married in January 1937. Dad was only seventeen when I was born in July 1937, and he turned eighteen in the following September.

Theirs was a love affair that lasted for fifty-three years. They died within three months of each other in 1989.

Moving to Balmain

In the late 1930s, we lived in the upstairs of a terrace house in Womerah Avenue, Darlinghurst. It was a very seedy area. My father told me he saw a person kicked to death one night, but no one got involved in those days, especially in that area.

All I remember about that time of my life is a friend called Diana, a swing that I had hanging in a doorway and a dinky to ride on.

We soon made the big move to Balmain. Mum was back ‘home’ and I was the new Balmain girl. We lived in a little house in Phillip Street and dad started work at Colgate Palmolive, where he was to stay for the rest of his working life. We only stayed there for three years as my sister Eileen was born and we needed a larger house.

This house was at number 48 Rowntree Street, Balmain. It was a two storey terrace semi-detached. It was a great house with a front veranda downstairs and a front balcony upstairs. Mum and dad lived there for the rest of their lives.

48 Rowntree Street

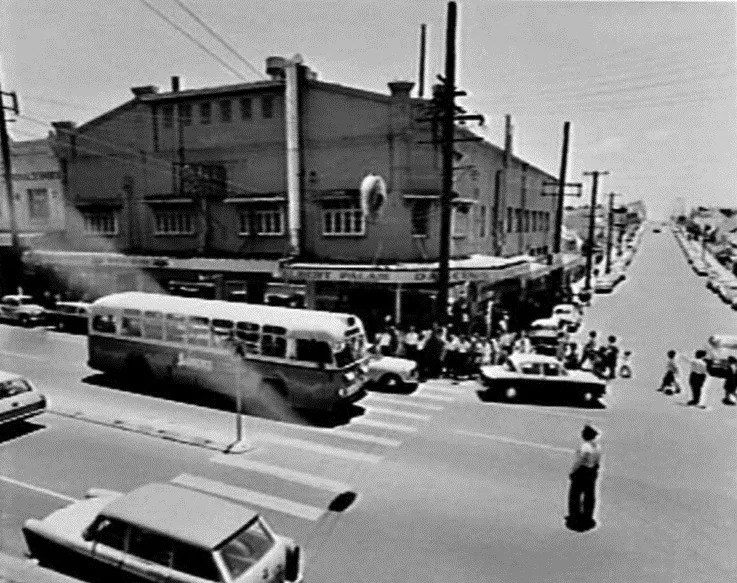

48 Rowntree Street Balmain, off the main road which was Darling Street, down towards Birchgrove where the trams terminated on the route from Sydney city. Other Balmain trams went down Darling Street to Balmain East and the ferry wharf. From here one could catch a Nicholson ferry to McLean Street, and then another tram to the city. The hill down Darling Street to the wharf was so steep that trams had to attach to a thing called a dummy.

Our house was rented, we never knew the owner and never cared. The rent was, as I remember, 125 and 6 pence – that’s $1.25. Balmain, I’d say, was a working man’s suburb. Most of the family men worked in the big factories like Colgate-Palmolive, Lever Brothers, Morts Dock, Cockatoo Island, Balmain Colliery, and Monsanto Chemicals.

Our house was just down from the main street, which was Darling Street. The Hoyts picture theatre was on one corner, with Balmain post office and police station on the opposite corner. Across from the Hoyt’s was a milk bar called Casamentos, owned by a Greek family. Across from that was the Town Hall pub. 48 Rowntree Street was my home from the age of 4, and that was in 1941.

It had a wood paling fence and was joined onto another house on the right, called a terrace. It had one big sandstone step up to the gate that hung on one rusty hinge for years. Then there were five more big sandstone steps that went up to the veranda. I fell off the veranda and crashed my head on the old broken hinge of the gate, spending hours in the emergency at Balmain Hospital. Eventually I received five stitches in my very sore head. I was lucky I wasn’t killed as it was a five-foot drop.

Mum and dad’s bedroom window opened onto the veranda and every week mum wiped down the windowsill and she painted black paint on the front step at our front door. There must have been hundreds of layers of black paint, but it was important to have a nice entrance to the house. The front door was mostly left open except in winter when we closed it to keep out the cold wind that came in from the harbour.

It was a great place. We only had a small back yard with a lane running up the side to other houses at the back, but we always managed to have a good time making gardens, mini golf courses and building cubby houses. Across the road from us there was a terrace of small very neat houses, and next to them a large empty paddock. This gave us a great view of the city and harbour, and also a good place to play, climb trees, pick mulberries, and blackberries, and chokos. That was until it was fenced-off and then eventually houses were built, but that was in the 50s after the war.

A step up on the blackened step of number 48 led us up a small hall past a bedroom doorway and into the living room. From here the beautiful cedar staircase led up to the other two bedrooms. Mum always had the linoleum floor in the hall and living room highly polished, all done on hands and knees with elbow grease and lino polish.

The living room really was a room for living. It had a small window that looked out into the backyard and a wonderful old fireplace with a mantelpiece which housed a lovely old clock that Mum won at bingo and that chimed every hour, bits and pieces, and family photos.

The fireplace was lit with a wonderful fire on cold winter days and nights, kept going with coal that was bought by the bag from the coalman, who came around every week in the winter. He carried the bag of coal on his shoulder up the side lane of our house. It was about 3 shillings ($0.03) a bag. We also scavenged around across the road for bits of wood to start the fire, and my Pop helped supply us with some wood from down the docks and other places.

It was great when we came home from school on a cold wintery day and Mum would have the fire burning. We could all smell it as soon as the door opened. It was wonderful such simple things that could make us so happy and content. We ate all our meals in the kitchen which was the only other room downstairs. We had a table with a stool and three chairs, an ice box, and a lovely kitchen cabinet with lead light doors. Across the back was a gas stove, an old fuel stove, and a small kitchen sink.

No hot water. We had to boil the kettle for water for tea, cooking or washing up. We did use the fuel stove during the war as gas was rationed like many other things. For instance, we needed ration coupons for lots of things, even clothes. Not that we bought much anyway as money was very short.

Once my mum went into Sydney city, or ‘into town’ as well called it. She had her handbag stolen and they got everything, including money and all our ration books. This meant we couldn’t get meat and some food.

I remember mum walking down the street coming home, she started crying and I went and got our neighbour from across the street, and Mum told her the story about what happened.

We rented for many years. When I was 18 in 1955, we had a chance to pay it off. My dad said he could not afford it so we all helped to pay off the mortgage. It cost a full 1000 pounds. Thirty-four years later we sold it for $210,000. (In 2019 it sold for $2.7 million).

Life in the new house

Kids at that time had to make their own fun as we didn’t have many toys. The toilet was right up in the far corner of the yard with none in the house. In the winter it was very cold and sometimes very scary.

We would nearly always go with each other. I had to take the little kids. Our bathroom was also out in the yard. It was not very nice. It had a dirt floor with a very large cement bath that looked like a horse trough in the corner. There was a copper. Mum had to make a fire under the copper to boil water to do the washing and get water for our bath.

She had to fill the bath with a bucket and it always got cold very fast. Mum had another two kids in the years after we’d moved to Balmain, a son, Norman, and another daughter, Gwen. Mum used to put us three girls in the bath together and Norman was put in after us.

In the winter we had our bath in a big tin tub in the kitchen. We didn’t always have money to buy wood for the copper. It was always fun in the tub and good to have a big pot of hot water poured over to finish off on very cold nights.

We had an open fire in the fire place in the dining room, which was our living room and only room other than our hall and bedrooms. So after a tub bath we would wrap up in a towel and dry off by the fire. It was wonderful and cozy.

Living at number 48 was very good. My grandparents lived down the street at number 101. Mum’s mother, Minnie, and father, William Watt — “pop” to us kids. He was a fun man, tall with white hair, and he taught me all about football, as football was a big part of the Watt family life.

Mum had three sisters and four brothers. I must tell a little about the brothers. George Watt played first grade rugby league for Balmain, and then played for Australia in the national team. The youngest boy, Neville Watt played for Balmain too. They both played in the position of hooker.

Pop used to take me down to Birchgrove Oval in my black and white football jumper which I loved to wear. He’d teach me how to play the ball and to tackle. He always said grab them around the ankles — they can’t run without legs — and all this to a 4-year-old girl. We were a Balmain football family. I was the first-born grandchild. I think he would have liked me to have been a boy but I loved him very much. He also sang all the wonderful old songs to me as he bounced me on his knee.

He was a good husband to my grandmother. He used to do all the washing for her and I never saw her do any work. She was always off to town. I don’t know what for.

Pop worked at Morts Dock for as long as I remember. When he got too old he still worked there as a cleaner. He died there on the job. When they used to drain the dock he would catch lots of fish and mussels and we would have a feast.

They moved from 101 to 123, just down the street, and stayed there until they died. One of my mum’s brothers, Jacky, and his wife and children, lived at number 125 next door. Lily, one of mum’s sisters, lived not far away in King Street.

We had lots of other cousins all over Balmain. The Watts family (not to be confused with the Watt family in the previous paragraphs) in Short Street was very close to us, Aunty Lilly and Uncle Archie, and all the girls and Alan. Aunty Lilly did a lot for my mum when mum was growing up — made all her clothes for dancing classes. Aunty Lilly and Grandma Minnie were stepsisters. That is a story on its own but I will come back to it later.

When I was 5 and dad went away to the war

All was well at number 48 but the Second World War, or ‘the war’ as we all called it then, was full on and then dad joined the Navy. It was January 18, 1943, and I was five. My sister, Eileen, was two. Dad went away on a train at Sydney’s Central Railway and we went to see him off. I remember waving to him and mum crying.

Everyone on the station seemed to be crying. It was so sad and I can still remember it today. When dad finished training he went onto the HMAS Kanimbla, a troop ship and off he went to war. There is more to this story.

And so to school

It is now time to start school. Birchgrove Public School is just around the corner from 48 Rowntree Street, in Birchgrove Road. I just have to walk up the street to Macquarie Terrace and there is the school, a very large brick and stone building. It is in a great position looking over the Parramatta River. I am in kindergarten and my teacher’s name is Miss Thompson. I love school so far. I am making lots of friends. We sit on mats and learn to count using milk bottle tops. We sing lots of songs, play games and learn to write our numbers on slate boards with slate pencils.

We all take our play-lunch and lunch wrapped in greaseproof paper and in a brown paper bag. All of us kids get a free bottle of milk every day. That’s good in the winter but in the summer it sits left in the sun and starts to go off. A lot of the kids in my class also have their father away at the war so we say a prayer every day to keep them safe.

When my dad was away in the war

My mother gets letters from dad when he gets a chance to send them. She waits for the postman every day and waits until I get home from school and reads them to my sister Eileen and me. She sits on the stairs and we sit at her feet.

We are happy that he is alright but mum always cries because we all miss him so much. We miss him singing as that always made us happy.

Being on a troop ship he did get home on leave and on two of those occasions mum fell pregnant, and so by the end of the war in 1945 we had two more babies — my brother Norman and my baby sister, Gwen.

There is only ten months between the two of them so mum had her hands full. My grandma down the street was a help and my mother’s youngest brother, Neville and youngest sister, Ruby, helped out.

When Gwen was to be born it was a bit much to expect any one to take on three little kids to mind. So one morning when we woke up, mum had gone to the hospital “to collect the baby”, as we were told. My grandmother packed our bags, and with the help of mum’s youngest sister Ruby, took us three kids to a ‘home’ where we had to stay while mum was in hospital.

The ‘home’ was called Scarba Welfare House for Children, at Bondi, and I now know it was run by The Benevolent Society. It was a home for orphans and poor kids in similar circumstances like us. We had to get there by tram as we had no cars. We went to Central Railway first and then had to change trams to get to Bondi. It was quite an ordeal with two little kids and a ten month old baby.

Because I was six, I went into the big kids’ section and Eileen and baby Norman went into another part. I was very sad and lonely. We had never been apart before and I missed mum very much.

I slept in a dormitory with other girls and the food was terrible. I do remember having raw sugar on thick porridge and no butter. Because of the war lots of things were rationed.

I did get into trouble once for wandering off to a restricted area because I saw some swings there. They had to have a search for me and I was punished with no dinner.

One night I was very unhappy so I was wrapped in a blanket and taken over to the baby section to see Eileen and Norman. After that I was taken over every other night just to see them so that I knew I was not alone. It must have been very sad for the children who had no one there and no one to come for them.

Note: In 2004 an Australian Government Senate Inquiry found evidence of institutional abuse of children at Scarba Welfare House. The Benevolent Society’ issued a public apology for this abuse in its publication, ‘Living at Scarba Home for Children (1917–1986)’. Click here to read this history and apology (opens in new webpage).

When mum came home from hospital it was time to get on with our life. We were very busy with two babies in the house and I think I had to grow up very fast and learn to look after myself in a lot of things. Without dad there to help we were a house of women. I became very bossy and always took charge with the little ones.

Eileen and I were very close. As we grew up we all became very much together, all Balmain kids sticking up for each other whether right or wrong.

In second class at school during the war, all of us children had to wear air raid bags made of calico all the time while we were at school. In them were earmuffs to protect us from noise in case of bombs and a peg to bite on. We had a drill where we all had to assemble in the hall and then march down to the basement of the school. Thank God we never had to use them.

We did get a very big fright towards the end of the war. There were a series of large explosions that shook the whole school. We all were told to get under our desks until we found out what had happened — so much for all our drills.

Next door to the school was the Balmain Coal Mine, one of Sydney’s oldest mines. At first the rumour was that a war mine had floated up the Parramatta River and exploded. It turned out to be a gas explosion and men were injured and killed. The school was closed for a few days until it was declared safe. This happened in 1945 and then the mine was closed for good.

It stood there for many years unused and boarded up until it was sold to a developer. Now in 2006 it is home for many families. I wonder if they all know they are sitting on a coal mine. I know I would not like to live there but it is a lovely position right there on the waterfront.

Dad coming home from the war

Dad came home in July 1946 when I was eight. He came into Garden Island on the ship loaded with soldiers all over the deck. It was a wonderful sight. The war was over at last. We all went down to see it dock.

At first we could not see dad but he was waving out of a port hole, and we saw him, and started to wave and call him. He saw us but we knew he could not get off until the next day as all the soldiers had to go first. But we were all happy and went home to plan a big welcome home party.

It was not as happy for a lot of others who were still waiting for news of their loved ones. All our relations and friends returned except one. That was the boy’s father who lived next door. The boy’s name was Brian and he was in my class at school. His dad was a prisoner of war in Singapore and they got news that he didn’t make it after waiting for months for news.

Brian was only eight so he never even got to know his father. His mum and also his grandmother lived next door so they were very broken up when they received the news.

I always thought of Brian as my first boyfriend. He was the first boy to kiss me when I was seven. I wonder where he is now. They moved away when he was about 15.

As life resumed back to almost normal, us Balmain kids did what most kids did — had fun. Because most of our families didn’t have much money, we had to make our own fun. We played games in the street with other kids that lived around us.

There were hardly any cars to worry about and the trams that ran up and down our street only ran every half hour, so we would play rounders or cricket in the middle of the road. It’s hard to believe that happening in the Balmain of today.

Being in hospital as a kid in mid-1940s

After Dad came home from the war and we all soon got into living a normal life again. That was in July 1946 and I was about to turn nine. I was in third class and that was the year I had my appendix out.

I took an attack of unbearable pain. Miss Rose was my teacher. She was a large lady who used to sit at her desk and we all used to laugh because we could see her big bloomers. One day when we were marching into school the elastic in her bloomers broke and they fell down. She just stepped out of them and put them in her bag. We all got into trouble for laughing and were kept in after school.

Getting back to my appendix attack, the pain was so bad I couldn’t walk. Two older girls were picked out to carry me home. Just as well I was a very small girl as we had to go about 500 metres. Luckily as we were just rounding the corner, my mum was just there with my grandmother. They were heading off to town for the day. Mum took me straight to the doctors and without even going home I was put into Balmain Hospital. I was operated on that afternoon. The doctor said I could have died if we had been any later in getting there.

Balmain Hospital was a beautiful hospital then, not a bit like it is now. The children’s ward was beautiful as all the walls had been decorated by Pixie O’Harris with lovely murals all around. Many years later I had my two children there.

The year before I had also had my tonsils out at the Children’s Hospital at Camperdown in Sydney (Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children).

My other hospital outing was at the Coast Hospital at Little Bay. It was also known as The Prince Henry Hospital and because of its beautiful position is now being sold as a new housing development.

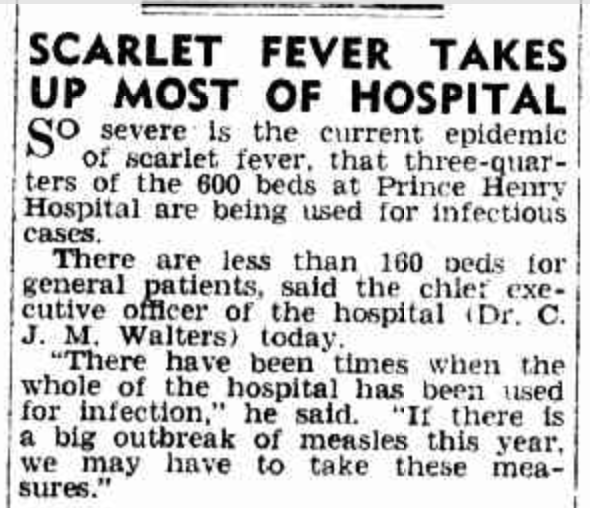

Back then the Coast Hospital was the place you were put when you were contagious. I think I was about eight when I was there. I was taken in an ambulance as I had scarlet fever. It was very catchy so I had to be isolated from the other kids. Mum put two chairs together to make me a bed in the front room until the ambulance arrived.

I was carried out of the house and all the neighbours were there to wish me well. I was very lonely in the hospital as mum and dad could only come on Sundays for a visit. It took about two hours to get there — first a tram to Central Railway then another to Little Bay — and they always brought the other children with them. Once there they could only look at me through a glass screen.

I had to stay there for six weeks. The nurses were very nice dressed in their stiff white aprons and veils. Once the red rash and the fever had gone I was not so sick so I just played and did some schoolwork, read books and sang songs.

Nurses and doctors came from all over the hospital just to hear me sing. It made me feel very special. I told them my dad taught me to sing and I knew lots of songs as he and I sang at home all the time. The song they liked me to sing was The Sandman Is Coming.

The stairs in 48 Rowntree Street

When you walked in the front door of our 48 Rowntree Street terrace house, the first thing that stood out at the end of the hall was the stairs. So many things happened on those old stairs.

Mum sitting on the stairs and crying every time she receives a letter from Dad who is away at War. I don’t know why she didn’t go further into the house. She just sat there and read them to us kids.

We were three girls and one boy but the house is always filled with neighbour’s kids and cousins who lived around us. We held concerts in the hall and we would all sit on the stairs and pretend we were in a theatre, or we’d play Bingo, especially on rainy or cold days.

Going up the stairs to bed sometimes we would be frightened especially after listening to ghost stories.

A good thing about our stairs was sliding down the banister. Many a bad fall but what fun! Mum would say “serves you right”.

Winters at the oval

Everyone in Balmain followed a football team, well everyone I knew. When I was young, say from about eight onwards, every Sunday (in the Winter, that is) from around 1pm the crowds would start the trek down to the Birchgrove oval. The trams would go past our house in Rowntree Street full of people hanging from the sides.

The trams all terminated at the water where the oval was. The people came from all around the area, suburbs like Glebe, Annandale, Drummoyne, Rozelle and Leichhardt. We all had our special teams to follow. Teams like Shamrocks old boys Glebe, Kodocks Gladesville and the Olympics. These were all junior teams playing in the President’s cup division.

Besides all the tramloads of people, people all walked for miles. Hundreds of them strolled past our house carrying blankets, cushions, bags of food and nibblies, and most times an umbrella as we would go rain or shine.

Our little band of kids never went with the adults, as we didn’t pay to get in.

We knew where all the loose palings were in the fence and that’s how we got in. It was always a great time. We didn’t spend a lot of time watching the football because we were out to make money. It was a well thought plan we had.

First we had to walk around to see the groups of people that were eating and drinking, and then we would split up and sit next to them. When they were nearly finished drinking we would ask if we could have the empty bottles. Each one we got was worth tuppence.

Days at Bronte Beach

In the summer all over Sydney, not just in Balmain, it was time for the beach. And what a time it was. We had more beaches to pick from than any other city in the world.

Bondi was the most famous to people overseas but to us Sydneysiders we all had our favourites and we flocked to them in the thousands.

There was Coogee, Maroubra, Clovelly, Manly, Cronulla, and lots of other smaller ones in between, not forgetting the northern beaches like Whale Beach, Mona Vale and Palm Beach. The northern beaches were more for the “silvertails”, and they were much harder to get to unless you had a car or lived in the area.

Every one of the beaches had a surf club and it was very cool to be in the clique with the surfer boys. I must say we could not have got on without them as they must have saved thousands of lives over many years. We Sydneysiders who were beach goers, knew how dangerous it could be with rips, sandbars and dumpers, not to mention the shark danger.

I haven’t yet mentioned our all-favourite beach. It was Bronte.

Our family went to Bronte beach every Sunday. Rain, hail or shine we would meet up with four other families who lived in the Bondi area. They were all old friends from dad’s days when he lived in Paddington and worked at the laundry. We remained friends with these families all of mum and dad’s life

There were the Browns — dad’s best mate, Les, his wife, Ruby (who I thought was very glamorous), and their only son Raymond. There was also the Samuels and the Shafers and all their children. We had great times.

To start with my sister, Eileen, and I would leave home loaded up with towels and the bits at 6.30am. We’d catch the tram outside of our house, get to Central Railway and then change trams to the Bronte tram. The trip took about one hour.

The reason for this early morning trek was to get our position at the beach. We always had the same “cubby houses” which were covered tables and chairs in groups of four. Eileen and I would get there before everyone else and put a towel or bag on each table. That would reserve them for our group for the day.

Mum and dad would arrive about an hour later with all the food and the younger kids, Norman and Gen. Al the other families would start to arrive about the same time.

Our “possie” was up on the big hill overlooking the surf. We had great times. All of us kids learnt to swim and surf in what was, and still is, called the Bogie Hole. It is a very large rock pool at the southern end of the beach.

We all loved the water and dad would put us up on his shoulders and let us dive in the water. It was crystal clear and we could swim under water with our eyes open.

After lunch we would all join in a game of cricket, rounders or shuttle cock. The sand hills at Bronte were a big attraction for us young kids. They were up the back of the park where there were swings and slippery dips. The sandhills were great fun as they were very big, or they seemed to be to us kids. We used to play hidings in the shrubs and climb through tunnels and spy on the teenage lovers in the bush. We weren’t supposed to go up there but kids will be kids.

At three o’clock the Sunday school would start. The people from the church who ran it would ring a bell and kids would run from everywhere for the half hour service. They would tell us a story, ask us some questions, sing Jesus songs and then we would all get a little text about the story.

After all that had finished it would be all back in the water for another swim.

The adults would play cards while all this was going on.

As the years went on I always swam in the big surf and was quite a good body surfer, thanks to dad’s good teaching, but I did like to hire a rubber surfboard and ride the waves. It would cost one shilling for half an hour. It was a real treat and I would try and find empty bottles to cash in to raise the money.

We would arrive home about 7pm all tired and most times sunburnt. Mum would dab us all over with cold tea to take away the hurt. We were all very brown as we had a mixture of vinegar and coconut oil that we would put at the beach — this is something we would never do today.

They were great days.

Stories from the 1950s

Teen years – when I was 14

Me: Why can’t I go?

Dad: Don’t ask me why when I say you can’t that’s it.

Me: But everyone else is going except me.

Dad: Well, their parents mustn’t care much about them.

Dad just looked at me with the sternest face and let me know the subject was closed. I couldn’t give up that easily so I started again.

Me: Don’t you trust me? Is that it?

Dad: Yes, I trust you when I can see you but I was young once myself you know.

I didn’t think 14 was too young to go to a party with boys and girls and no parents at home.

Me: Please let me go.

Dad: I won’t stand here and argue with a child. The subject is closed and that’s that.

I sneaked out and went anyway. Dad was waiting on the corner for me when I came down the street after midnight. Could you trust me? Not really.

About the party, it was awful. Not worth any of the trouble it got me in when I got home.

We’d always had parties at our house with friends and neighbours, we played games and had sing-alongs and had lots of fun. I don’t know what I expected at this party, but I didn’t know any of the boys and they all seemed older. The only girls were from school but only two of them were my friends.

We had some food then the boys had bottles of beer. Next two lights went off and everyone seemed to pair off.

A large boy grabbed me and tried to kiss me. It was really horrible. I remembered running to the bathroom in panic and locking myself in. I was in such a panic I had a nosebleed, and it wouldn’t stop.

Someone heard me crying out. I wouldn’t open the door and I was frightened. The rest is all a blur. One of the girls called to me and took me away to another room in the house.

The party broke up and I was not very popular after that episode. I didn’t get asked to any more parties. I saw the boy one day not long after and he was an Italian boy working in the fruit shop at Rozelle. He didn’t see me, and I never went to that shop again.

Swimming and smoking

I’ve been a swimmer for as long as I can remember. We went to Bondi and Bronte Beach where we surfed. Mum took me at age 3 to Redleaf Pool at Double Bay where she taught me to swim. The four of us kids were in the Balmain Swimming Club at Balmain Baths for many years. I trained with Dawn Fraser, who was one of my best friends, and we went all over Balmain on our pushbikes.

(Dawn Fraser Baths)

I went to Riverside High School in Gladesville for girls only. We learnt to cook, clean, and to make beds. I was good at the swimming carnival but only managed to get second place in the main 50 metres race. However, I won the diving and went onto Sydney Olympic Pool and the state diving championships, but didn’t come a place.

I smoked my first cigarette down at Elkington Park with Dawn Fraser and burnt a hole in my jeans. I tried to cover it by cutting it out and making it look like a tear but, silly girl me, left the burnt bit on the floor. Mum found it and showed it to Dad when he came home from work.

What a lecture I got but it made sense and I never smoked again. He said boys wouldn’t want to kiss me and I’d have yellow rotted teeth and yellow nicotine stains on my fingers. And I’d get a belting if I did it again. Very stern but sensible my dad was.

Things changed. I went to work!

The last years of my childhood and believing the best years were over. What could I do? I was always told I was a dunce. Not much in the brain department I think. I couldn’t do maths and I wasn’t good at English. Two of my so-called friends from high school had a job in a factory nearby, one worked in the office and the other sewing. Yes, I could do that. I loved to sew.

I could not wait until the end of the term when I was to do my Leaving Certificate. I hated being at school and knew I wouldn’t pass any way. I was told by I-don’t-know-who that I could leave school at 14 years and 10 months. So on the way home from school I went to the sewing factory, called Hansel and Gamble.

Full of confidence I walked into the office and asked to speak to Mr Hansel or Mr gamble. I think they must have thought me an idiot so they asked me into their office. Here I was in my school uniform telling them I was leaving school next week and I would like a job.

I told them I loved sewing and made most of my clothes, and I would be a good worker. They must have felt sorry for me and said they would give me a try.

Next day I went to school all dressed up to leave. I was called down to the head mistress’s office. “Why are you not in uniform?” asked Miss Telley. I told her I had a job and was starting next Monday. To my horror and embarrassment I was told I could not leave until I turned 15, and to “get back to class”.

I was devastated and embarrassed and I had to face everyone and turn up for the next two months. I could have just died.

The next day and after school I turned up at the factory and had to tell them I couldn’t come to work after all. Mum and Dad had to be told that I had a job as I hadn’t mentioned to them anything about it. Explaining my mistake to Mr Hansel and Mr Gamble they said because I was so enthusiastic they would welcome me back as soon as I turned 15.

So two more months and my life as a grown up would start at last! And so it began.

Off to work for Joan

The factory was in Elliot Street, Balmain. Not very big, just like a shed from the outside with a warehouse and the office downstairs, and then up to the work room. There were about 20 rows of sewing machines of various kinds and a long table with fabric all laid out ready to be cut and sewed. Everyone welcomed me and right away I loved it.

My first disappointment came very fast as Kathy, the floor-lady, said it will be a while before I could work the machines because of work laws. We made all sorts of items such as handkerchiefs and tea towels, baby bibs, scarves and an assortment of other things. Some of the lady workers were old to me. At that time, old was about 30 years old!

There were a few men and boys, one quite good looking, and then a mechanic who kept all the machines in working order.

It didn’t take me long to get to know how everything was made. At first I had to cut and trim cottons. There were jobs for ironers, packers and folders. We worked 8 am until 4.30 pm 5 days a week. My starting pay was £3.2.6 (about $6.25 a week) for 40 hours. We had lunch for 30 minutes and morning tea for 10 minutes.

We had a radio going every afternoon from 2-4 pm. It was called The Workers Hour and anyone could request songs to be played. It was all very pleasant and I loved it. We sang along, talked and sewed.

When you got better on the machines we would earn more money. It was called piece work, the more you did the more you earned. It was a good incentive not to talk so much. It was heads down and bums up.

It was about three months into the job when a new boy started. He was to be trained as a cutter as the other one up and left. The one that left was quite a looker and a lot of the girls fancied him. The new boy was very young looking, a bit fat, and sort of looked Italian. We were not impressed.

Not long after he started, he and I became friends as he worked near my machine and we got to talking a lot. I soon found out he was not Italian but Irish. I let him borrow my pushbike each day as he lived nearby and went home for lunch.

This boy was to become ‘my Frankie’ for the next 60 years, the love of my life and father of my two lovely children. Who would have thought this would happen?

Not so fast!

It was not love at first sight but good friends with a few things in common, and lots not in common at all. I loved to swim and surf, dance and sing, go to football games and picnics, and parties with friends. Not Frankie.

He was very different from all the other boys. Not an Aussie Balmain boy.

A cautionary tale from 1953: What a night!

There he was. Standing smack back right in the middle of Rowntree Street, Balmain at 3am on Sunday morning. He was dressed for the occasion, all in his best checked flannelette pyjamas and felt slippers. My dad. Oh no, was all I could say.

But maybe it would be a good idea to go back in time, not too far. It all started on the Saturday afternoon when a girlfriend from work said we should go out dancing to the Albert Palais in Leichhardt, the best dance in Sydney on a Saturday night. They had a great band playing, the best swing dance songs with the coolest singers. I was always a bit nervous going out with someone new but Pat was older than me. I always thought she was a nice Catholic girl so I was excited and looking forward to the dance.

In case my reader doesn’t know how the dance hall operated in the 1950s let me set the scene. Not many went with partners because we all hoped we would meet the boy of our dreams. It was a strange set up as all the girls would stand or sit at one end of the hall and all the boys would be on the opposite side. When the music started the boys would make their way across the floor and us girls would wait and hope one would ask us to dance.

Of course, the regulars knew each other so they would get asked first. The rest of us would get the leftovers. It was very nerve-racking and also embarrassing for the odd ones left without a partner. Well, let’s get on with our story.

I’m not too bad looking and I usually ended up with a reasonable partner. One extremely good-looking guy came over to me and I couldn’t believe my luck. But my luck was soon changed when he said to me, “Would you like to dance?” Of course I said yes, and he answered, “Well maybe someone will ask you” and walked away.

I was so embarrassed. I felt everyone there had seen and heard but of course, they hadn’t. I could have just sunk into the floor. The music was loud and great, and luckily another boy, not as good looking or as cool as the first one, but very nice, saved the day. He asked me to dance and said not to worry as he would love to dance with me.

11pm: we had a great night at the Albert Palais. Great music from the big band playing the top tunes of Glen Miller, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw with lots of dances like jiving and the dance of the time, the “Albert Crawl”. As we all left the dance in our assorted groups, some with the boys they had met that night and others, like my girlfriend and me, alone but in a happy mood.

We headed for the taxi rank and joined the queue. Pat said, “We’ll be here all night. Let’s walk down the street a bit and try there.” As we left the throng of people on Parramatta Road and headed across Balmain Road, a couple of nice looking boys approached Pat and I and said they could give us a lift to Balmain in their car. I hesitated but Pat said they looked nice enough, why not?

“Don’t ever get into a stranger’s car.” The words were ingrained into my brain by my dad since I was a small child. But where does common sense go when it’s needed most? I was with Patricia, wasn’t I? She was older than me and a good Catholic girl. She wouldn’t lead me astray, would she? How wrong could I be as things progressed at a rapid pace.

“Yes, we would love a lift, thank you,” said Pat.

So we headed around the corner into Balmain Road to their little Volkswagen car. We would be home in fifteen minutes, what could go wrong? Pat hopped into the front with the two boys and I jumped into the back only to find myself net to another fellow who was half asleep.

“Oh no,” I said, “Let me out.” But the car only had two doors so there was no way I could get out. After introductions like, this is Tom, Dick and Harry (Ha!), we headed along Balmain Road towards home. So far so good. I started to relax. It was still only a quarter to twelve and I’d be home by midnight, great.

We were at Rozelle, about five minutes from home. To my surprise Pat in the front of the car was smooching and kissing with Tom, who we had only just met. Then it was suggested that we stop somewhere and have a coffee or hamburger.

“No way,” I said. “I have to be home by twelve.”

“Oh come on, don’t be a nerd.”

“Well ok,” I said tentatively, “but where will we find somewhere open at this time of night?” I just thought he meant local.

“We’ll get coffee at Kings Cross, let’s go there.”

Hell no, I would never get home. I couldn’t get out and what could I do? By this time, Harry in the back was waking up and starting to make advances. He was at least nineteen or twenty and I was only sixteen, and starting to get scared. While all of this was going on, we were headed to Kings Cross and beyond, down to the beach at Rushcutters Bay which is down behind the movie theatre. Why are we here?

It’s now 1am. I’ll get killed when I get home, if I ever get home! We pulled into the park and parked. Pat said, “I won’t be long,” and got out and headed along the beach wrapped in the arms of Tom.

“What the hell is going on?” I asked. “I want to go home.”

“Shut up, they won’t be long…why don’t we fill in some time together?” said Harry, as he kissed me and put his hand up my skirt.

I started to panic and I pushed the front seat forward and got out of the car. I walked up to the main road but didn’t have a clue where I was. I was standing there crying, not knowing which way to go. I don’t know how long I was standing there when the car drove up to me.

Patricia was back in the car and said, get in we’re going home. By this time I was so distressed I was ready to go home. I got in and hunched into the corner of the car and sobbed all the way to Balmain. I was told not to be a sook and to shut up.

As we came to Patricia’s house they dropped her off first and continued down the street to where I lived. As we came down the street I saw my father in his pyjamas standing looking up the road. I said stop and jumped out as fast as I could, grateful to be home but terrified of my father’s anger.

To my surprise he just walked up to the boys in the car and said something, I don’t know what to this day. But he turned to me with tears in his eyes and said, “Don’t say a word.”

He never mentioned it again.

That was 1953. Now my dad has gone and as I write this I have my own teenage daughter. It’s only now I know how hurt and worried he must have been and what I put him through in just one night of terror for me and for him.

Stories from later on

The last party for Dave and Doris

Although they are no more, in my heart, my mind and my soul, they live. The love my parents shared was always obvious in a non-obvious way. Not with cuddles or kisses but in just being together with looks and little touches and smiles. At dad’s 70th birthday party in 1988 the love was just as strong as I remembered as a child.

There was one morning when I came down for breakfast and mum had a tear in her eye.

I asked, “What’s wrong, Mum?”

“Dad went off to work and I didn’t get a kiss goodbye. He always gives me a kiss before he goes.”

She was miserable all day until he came home.

I guess there was a reason for no kiss, but I never knew why. I never heard them have a fight or say a bad word to each other.

Dad was the loveliest person to his children, but I don’t know if the other three felt it as much as me as I was the eldest by four years.

Mum was always placid and did everything for dad, as women were expected to in that era before liberated women told them to stop.

Dad never took advantage of her doting ways and, in the last years of their life after Mum had a stroke, he devoted the total amount of his life left to looking after her.

At the last birthday party they had together the love was still there, between them and in the whole room full of their family.

That was the party where the birthday cake fell behind the cupboard. But that’s a whole other tale…

Some memories and points:

I have travelled the world many times since 1977 – USA, UK, Europe, and New Zealand – and I love cruising.

I have two children Melanie and Russell.

I have four adult grandchildren.

To be continued…

Life and Times of a Balmain Girl ©2024

Website contact: branxton@gmail.com